Revelations in turbulent times

text_fields.jpg) Where are prison diaries of the day? Why don’t political prisoners write diaries, so that we know what’s taking place in those hell holes? Are prisoners of the day discouraged from offloading their everyday experiences or inner most thoughts and emotions?

Where are prison diaries of the day? Why don’t political prisoners write diaries, so that we know what’s taking place in those hell holes? Are prisoners of the day discouraged from offloading their everyday experiences or inner most thoughts and emotions?

Are these ‘caged’ men and women reduced to such levels of hopelessness that they don’t want to yield the pen or else try to key in, that is, if computers and laptops are even available in the prisons in these ‘developed’ times we are living in? Also, is there that basic freedom for the imprisoned to write fearlessly and freely and in that ongoing way, day after day, in that imprisoned state?

What’s got me all too provoked to throw around these queries , is this recently published book - ‘Prison Days’( Speaking Tiger) by Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, with a foreword by her daughter, Nayantara Sahgal. This prison diary was written by her in the early 1940s, and as one reads through what comes out is the ground reality of that historic phase when hundreds of the who’s who were imprisoned. And these included Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and members of his family.

To quote Nayantara Sahgal from the foreword – “My mother, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, wrote this prison diary during her third and last imprisonment under British rule. It begins on 12 August 1942, six days before her forty-second birthday. World War II was on. Allahabad, like the rest of the country was under military rule. Arrests and imprisonment took place without trial. Several lorries filled with armed policemen arrived that night at Anand Bhawan at 2 a.m. to arrest one lone, unarmed woman, who, along with her husband, Ranjit Sitaram Pandit, and her brother Jawaharlal Nehru, had committed her life to the non-violent fight to free India from British rule, under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi… My father was already a prisoner in the Naini Central jail in Allahabad, where she was taken, and he would later be transferred to a jail in Bareilly, where he would fall mortally ill, and finally be released only to die. My uncle was imprisoned ‘somewhere in India’. It was not made public until much later that he and other leaders of the Indian National Congress were held in the Ahmednagar Fort. My older sister, Chandralekha, aged eighteen, and my cousin, Indira Gandhi , aged twenty-five, were arrested later and taken to Naini Jail.”

In this book, there is no mention of physical tortures inflicted on Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit but then as she writes in the preface, “This little diary does not attempt to record all the events which took place during my last term of imprisonment... the treatment given to me and to those shared the barrack with me was , according to the prison standards, very lenient - the reader must not imagine that others were equally well treated. When the truth about that unhappy period is made known many grim stories will come to light, but that time is still far away.”

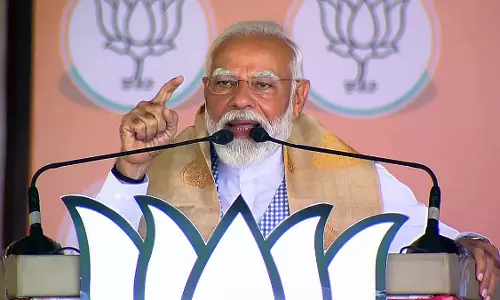

After one has read through this slim book, one wonders why does the Rajasthan Government plan to remove an entire chapter on Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru from the school text books. Also, why there’s that move by the present rulers of the day to bypass or ignore the role played by Nehru’s entire clan in the freedom struggle of this country. Should the Right-Wing rulers intrude into our history and trample upon the crusade undertaken by the who’s who of that era to fight the British till we attained our freedom! Can the country’s very history and historical turns be twisted by fascist forces?

FAROOQUE SHEIKH - actor with a difference!

Farooque Sheikh would have turned 70 on March 25...and I sit keying in, nostalgia overtakes. I met and interviewed Farooque Sheikh twice - once in the 90s and then around 2005, after I had heard him speak at one of the seminars here, in New Delhi.

He was at his out-spoken best. He didn’t mince words, describing and detailing the hard ground realities of Bollywood. He had told me that successful film-makers in Bollywood have big budgets but little sensitivity and with that cinema has become a commodity to be sold. He lamented there were no film producers of the calibre of K. Asif , Guru Dutt, Bimal Roy and Mehboob sahib. “Mehboob sahib had no money yet his passion drove him to make films and the fact that Bimal Roy lived in a rented accommodation all his life. Or the fact that it took M S Sathyu full 20 years to repay the debt he took to make Garam Hawa. That level of commitment is missing … today’s film producer simply goes by the fact whether the film will be a box office hit. There are too many business interests involved.”

Farooque Sheikh had also focused on the typical perceptions that the Indian cinema portrays. “Community perceptions in our films have always centred around stereotypes: the Christian character is a girl dancing or wearing short skirts with indications that she's a fast girl, the Parsee is shown as blundering. The Sikh is either a soldier or eating parathas; none of the screen portrayals show him like Dr. Manmohan Singh. In the case of Muslims, the characters are hardly believable. Why do they portray the Muslim man as always wearing a lungi and a vest! Or as a ghaddar. As a token, one of them will be very patriotic so that the entire community is not misunderstood. The other stereotypes — with 300 adaabs in one film and women wearing ghararas or cooking kormas — are also absent in an average Muslim household.”

Towards the end of that interview when I’d asked him to mention any one film-maker who still holds out some hope, he’d said –“Only Anand Patwardhan. He has fought the system. And fighting the system is not an easy task.”